Advance care planning in MS: an MDT approach

Event reports'We don't just want to live a good life, we want to have a good death.'

It was with this statement that Dr Lorraine Petersen, Medical Director and Consultant in Palliative Care began her session on advanced care planning in MS.

Lorraine summed up her views on optimal discussions, first providing a detailed reading list which provided a framework for her talk.

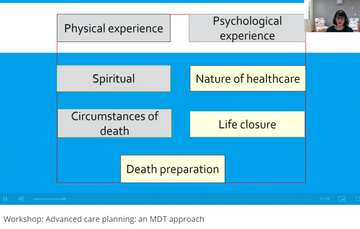

Fig 1: Slide from Lorraine's session: '7 domains that are important when we think about dying.'

Lorraine discussed each area, highlighting that those shown in yellow are more recent themes to arise.

Dr Lorraine Petersen, Medical Director and Consultant in Palliative Care

When is a good time to talk?

Lorraine was clear that, ideally, discussions are started by the patient when they feel ready - but was clear that research suggests patients believe it is for the health care professional to initiate these conversations. With this in mind, Lorraine shared a number of occasions in a person with MS's journey where beginning, or continuing these discussions might be appropriate.

- When life-prolonging or life-sustaining treatment begins. In MS this might feel too soon - but it could be an opportunity to highlight that these discussions will need to be had, to open the door to those discussions later on, and to start the patient perhaps mulling their preferences over.

- When a decision is made to stop disease-modifying therapy. This is a key change in a person's journey with MS and provides a good opportunity to pause and reflect, and to plan for the future.

- Self-recognition of deterioration in their condition, or perhaps a continued deterioration, perhaps a series of events, or the change of circumstances like moving into sheltered accommodation or requiring at-home care.

- After a life-changing event can be a trigger for a conversation, such as an emergency hospital admission or a significant change in personal circumstances. However, timing is essential, and whilst the event is going on it can be too traumatic for the individual to have a full conversation

Who should be having these discussions?

Lorraine was clear that there is no one individual or role responsible for having discussions around advance care and future preferences, and the right person is dependent on the questions that the person with MS has, at that time.

Dr Lorraine Petersen, Medical Director and Consultant in Palliative Care

For example:

- Questions about the sort of medication management that a person might need towards the end of life might be best discussed with a neurologist.

- Questions about being cared for in their own home might be best discussed with a GP.

- Talking about the different healthcare environments available to a person, and the options and outcomes that are likely in each might be a conversation best suited to a specialist nurse.

The ultimate aim, across all these discussions, taking place at different times and with different professionals, is to create an unambiguous care plan. Lorraine was clear that the plan must be good enough to be legally binding and very clear for the next healthcare professional who views or adds to it, so that they are able to follow the person's wishes.

The conversation process

Lorraine stressed the need to start a conversation, not from a standardised 'beginning', but from where the person is 'at' in that moment, taking into consideration their thoughts about the future, and finding out their motivation for the discussion.

She shared some useful questions which can be used as prompts, adapted to a situation or useful to consider before framing a question or starting a conversation with someone.

The responses to each question should trigger a certain pathway for that conversation to run via. For example, if someone says that they do not like to plan ahead (question 2), this may halt the discussion, or prompt a different way forward, such as signposting or sharing information for the person to look at or think about as they choose, in their own time.

Questions / prompts to support advance care discussions

- What do you think about your condition at the moment and where you are?

- Are you someone who likes to plan ahead?

- What makes your life go well?

- What is important to you in your life?

- How do you feel your quality of life is now?

- Is there a line that, if crossed, would make you feel differently about your choices?

- What will make this conversation useful to you?

Lorraine shared helpful ways to frame the conversation, particularly if an individual seems reticent to respond, or uncomfortable with the discussion. She noted that advance care planning can be a positive opportunity - not only thinking about what a person does not want, but what they do want.

Helping the person to see this as an opportunity to make their own choices, or perhaps to help give their family confidence that they will understand how best to act in the future, can be useful view points.

Lorraine talked through some of the nuances and difficulties in advance care discussions. These included:

- The parameters to supporting people's wishes, including differentiating between choice of treatments and place of care,

- Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) and the nuances that can be at play in ensuring they are valid and remain so, including appointing an attorney, discussing their wishes, and the importance of appointing people 'severally', not 'jointly'.

- Advanced decisions to refuse treatment (ADRTs) take precedence over a LPA.

Clinical planning in practice

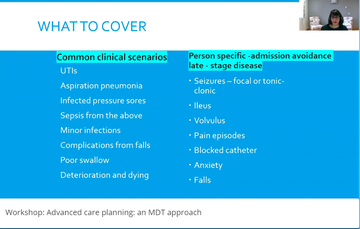

Lorraine took time to go through various clinical scenarios, with her key areas of discussion summarised in figure 2.

Figure 2: Lorraine's slide from her talk on ACP (minute 43)

She also gave examples of how she might write clear statements within someone's advance care plan, highlighting that statements around what is wanted or what is not wanted should be written in preference order as shared by the individual.

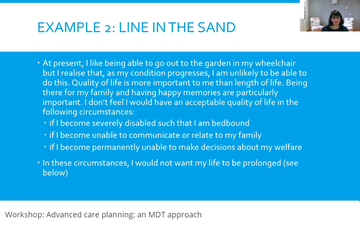

She shared the concept of 'the line in the sand'. She highlighted how important it is to ascertain a person's 'line in the sand' - the point at which their wishes would change - and why it is essential to outline clearly what that would look like for an individual, as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Example of a statement expressing a 'line in the sand.'

Lorraine closed the session with her tips on completing an ACP, and some examples of unintended circumstances caused by unclear or incomplete planning documents. She also highlighted that it is essential not to inadvertently sign a patient out of treatment that they may wish to have, for example, treatment for minor infections during a hospital stay whilst they still experience good quality of life generally, versus at a time when their 'line in the sand' has been drawn and they would choose not to have further treatment.

Tips on completion

- Use the patient's own words and phrases to make it their document

- Write advance statements and refusals separately

- Consider withholding and withdrawing treatments

- Be very specific and use medical language (applicability)

- You do not need to write something about every treatment

- If you cannot predict the situation then state the basis on which that decision would be made

- Do not accidentally sign the patient out of treatment

- Write a sensible review date and arrange for dissemination

Related articles

Encouraging excellence, developing leaders, inspiring change

MS Academy was established in 2016 and in that time has accomplished a huge amount with exciting feedback demonstrating delegates feel inspired and energised along their personal and service development journeys. The various different levels of specialist MS training we offer are dedicated to case-based learning and practical application of cutting edge research.