Before you watch this webinar

Enhancing your learning experience begins with understanding you better. Collecting data enables us to tailor our educational content specifically for our audience. Discover more about how we handle your information in our Privacy Policy.

Event

Alzheimer's disease & dementia – Care and support in a COVID-19 world: Nurse perspectives from the frontline

Summary

Overview

The core themes being addressed are, as in the previous webinar:

- Clinical care

- Adapted working

- Complex decision-making

A number of the questions responded to this week were posed at last weeks’ webinar.

Clinical care

Last week we discussed some of the potential risks of cholinesterase inhibitors in PwD, citing concerns around cardiac risk and potential worsening of hypoxemia as cardiac arrhythmias have been seen in people with COVID-19. In view of this, would you use AChEIs for BPSD instead of antipsychotics?

Gregor was clear that nothing we have, in terms of medication, is particularly effective and many have hazards.

- If you are considering medication, he urged a return to examining other options and factors around relationships, environments, addressing delirium and such, saying that there is likely to be more value in doing this than in prescribing a medication.

- If you are picking a medication, the side effects need to be manageable and not make the overall situation worse.

- Memantine can be used in this situation. It won’t be an immediate solution, but if you can wait for the effect to build up, it is fairly well tolerated. Some people can develop delirium or disturbed behaviours as a side effect which can indicate COVID-19 so we do need to be careful here.

Follow-up question: If someone needed to start on a new ACHEI due to the situation described above, or, they had received a diagnosis but had not yet received a prescription, how would you manage that situation?

Gregor explained that Memory services are trying to be available again but remotely, which is a challenge.

- As with any medication prescribing, the decision is a weighing up of the risks versus the benefits. At the moment, the risks are higher because we are not able to monitor patients effectively.

- It might be better to defer and look at medication in a few months when we may be able to monitor more successfully.

Long-term care facilities are high-risk settings for severe outcomes from outbreaks of Covid-19, owing to both the advanced age and frequent chronic underlying health conditions of the residents and the movement of health care personnel among facilities in a region.

How many COVID-19-related deaths in care homes are people with dementia?

Joe responded that there are a lot of problems with data from care homes.

- Lots of people have dementia but are not formally diagnosed;

- There is a huge variation in practice across care homes,

- There is very limited consistent testing of COVID-19 at the moment.

- All residents in a care home are susceptible to the same level of risk as elsewhere in the community.

- 60-80% of care home deaths are likely to be people living with dementia.

- We know there are challenges of managing people with dementia in care homes given difficulties maintaining social distancing and the proportions are likely to be higher.

- The study into care homes in Washington State provides an interesting insight into how many patients have symptoms. Over half of patients in the Washington Care Home had symptoms, highlighting the need for testing. 25-35% died, some in hospital, some in care homes, and this underlines the risk of mortality.

How many COVID-19-related deaths in hospitals are people with dementia?

Joe noted that there is a quoted statistic that 6% of people in hospital at any time have dementia, however we know that under COVID-19 people who might normally be admitted with dementia are not.

- A UK study found that 10-15% of 16,000 patients testing positive for COVID had dementia but we know that hospital recording can be flawed, and that dementia itself is underdiagnosed so I imagine that these statistics are very conservative. We need to be careful as to how we review these statistics.

How can we better support the solo care partners at home with their mental health, who now find themselves in very difficult situations with no respite?

Ira highlighted data from Alzheimer’s Society Ireland via Bernadette Rock. Key findings from their survey of the core challenges to supporting a person at home on their own were:

- Loneliness and isolation

- Lack of routine and boredom

- Anxiety and depression

- 95% of community champions felt people with dementia needed daily practical or emotional support during this pandemic

Diana noted a huge similarity in her own experience. She noted that 500 year ago, during the bubonic plague, caregivers of the era dropped from exhaustion – and that we are witnessing the same problem. Practical ideas to help included:

- Providing access to information; those who are not very internet savvy are missing a lot of access to information which could support them.

- Letting people need to know that they can ring and talk, or vent, and that someone will listen to them.

- Offering practical help getting shopping, walking the dog, and such can take away the strain and stop them from being overwhelmed.

- Most people feel that the intervention they welcome most is a daily call checking how they are, so facilitating local peer support could make an impact, even just a WhatsApp group, to help them feel a little less lonely.

- Activity planners can also be really helpful, with three weeks’ worth of a good balance of activity to support the ideas for carers.

- Telling people that they can take moments where they put themselves first, even if it is just 5 minutes.

Follow-up question: Do you think there is a role specifically for memory clinics to do more and proactively contact families for a checkup and ongoing contact?

Diana responded:

- Yes, and I would advocate a practical approach. Memory assessment services go from assessment to diagnosis and signposting, whereas memory clinics pass the patient on after diagnosis. We cannot pass patients on at this time. We need to keep in touch with them ourselves, and make them feel valued and supported.

- Many people feel that they are imposing on the health service – people are delaying accessing the NHS when they have a stroke! We need to allow them to feel that they are important and they are a priority too.

- We need to start using telehealth, being creative, training ourselves how you do telehealth properly and hold a conversation with a purpose. This situation is not ending soon and people will be scared to come into clinics – we need to find ways to do this now.

It appears that there may be neurologic complications related to COVID-19. Can you please discuss this and any potential relationship to worsening dementia now, or increasing the risk of dementia in the future?

Joe noted that there has been emerging information over the past few weeks on this topic.

- In one study, over a third of patients testing positive for COVID-19 had neurological symptoms of some kind, from loss of taste and sense of smell, dizziness, falls, muscle weakness, or even strokes as a consequence of, or comorbid with COVID-19.

- The initial outbreak of SARs demonstrated the ability to travel from the respiratory tract into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and into the brain. We have not seen that with COVID-19 yet but we may. (MS Academy ran a webinar on CSF and biomarkers of COVID-19 in MS patients and some information is transferable here.)

- There is an evolving opinion on how COVID-19 presents, particularly in older people. We need to look at atypical presentations, beyond a cough and fever.

- Delirium is a significant risk factor for dementia, can be a first symptom of dementia and is being seen as a symptom of COVID-19. If you see someone whose dementia seems to have deteriorated or a patient who has cognitive symptoms for the first time you should be thinking about COVID-19 and underlying dementia.

Adapted working

It is also reported that people with dementia are being sent home from hospital without adequate home and community support in place. How can we manage this?

Karen noted that, ordinarily, people with dementia do not always get the services and support they need despite clear NICE guidance on step up and step down services, but in light of COVID-19, these situations become more complex.

- People with dementia are being admitted into care homes inappropriately because it is more difficult to discharge them home, especially if they live alone.

- Some acute hospitals have rapid discharge teams expediting people out of hospital within 24 hours and enabling step down services, although there are reports that in populous areas these resources are overstretched and not as available as they should be.

- Families and carers need to negotiate with hospitals and contact the services that are still available locally, such as the Admiral nurse dementia helpline (which is internationally available but UK-based. 364 days each year).

Last week we talked about memory clinics starting to work remotely, and specific questions about ‘teleneuropsychology’ or remote cognitive testing are coming up. What guidance is out there and should we be engaging with it?

Joe responded that this has been explored in little pockets for a number of years, but COVID-19 has expedited its use.

- He noted that NHS England have advised against its use with any individual over the age of 70 but that in the current circumstances, the Royal College of Psychiatrists have recognised we may need to make exceptions.

- RCP have information on this

- American Psychological Association have provided a free online course you can do to become comprehensive

- The Clinical Society for Neuropsychology has useful summary guidance on teleneuropsychology during COVID-19.

- Bear in mind the limitations posed. A lot of these tests have not been validated in these formats. The standard of care must not be compromised by this median. Where there is any doubt with a diagnosis or management plan, you must follow up with a face to face call – tele-consults should be an adjunct rather than a replacement.

- There are challenges around consent and inadvertent coaching of responses – who else is in the room with the patient?

- There is not the same certainty in these tests as we can when we’re in the room – we need more research in it.

Ira noted we need to be aware that we have to do something, especially with patients who might be reluctant to come into a clinic for a while.

Gregor summarised the online MoCA which can be administered within 10-15 minutes by someone who has had a small amount of online training, or an abbreviated MoCA which could also be considered.

- Video consultation is ideally needed and many places are looking at how to do this for people, and will help with using the standard MoCA too.

- There is a validated MoCA for people with visual impairment, so the things you need to see are taken out and it’s a score out of 22, which is therefore possible to do via telephone, although you cannot see if the person is being prompted by someone in the room.

- Whatever is used, Gregor encouraged people to bear in mind the purpose of doing the test. There is always a degree of interpretation to what you are seeing and it is about how people engage and interact with the test, not just the number obtained on the test. It should always be done alongside the clinical history and the wider picture of the patient.

Ira added that aging related dual-sensory loss is common in people with dementia, and with this we lose even more validity on the tests. There is some important guidance available around this found here.

Complex decision-making

Some families are now finding it difficult to cope in managing the care of a person with dementia at home in restricted environments. In normal circumstances, they would consider admission to a care facility. They are frightened to do that now and several facilities are not accepting new residents. What kind of guidance is there for families in this situation?

- Diana began her response by asking ‘whose decision is this?’

- She highlighted that there should be proper care planning for anyone transferring to a care home, and was very clear that any transfers should be temporary.

- We know transferring to care or nursing homes has a deleterious effect on people; I would advise people to try and hang on in there, not to transfer because of coronavirus; find other forms of support, find other solutions.

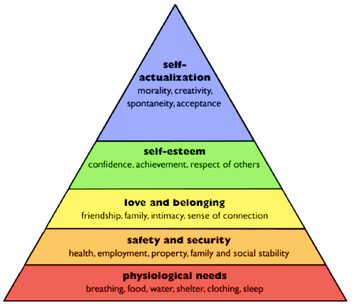

- Diana shared Maslow’s hierarchy of need (fig 1), at the moment we need to prioritise safety, security and survival. We need to help people to manage this at home, as much as we can.

Figure 1: Maslow’s hierarchy of need

There are reports of a rise in the number of Do Not Resuscitate (DNR CPR) orders for older people being admitted to hospital, particularly since they are often unaccompanied by families. Please provide some guidance on how this can be managed and what families can do to ensure their views and the views of the person with dementia are respected.

Karen shared that this is not only happening in hospitals but that there have been cases where GPs have sent out requests for DNAR to all their dementia patients.

- The British population tend not to talk about death and dying, and it is currently a situation where death and dying is facing us clearly.

- We need to have conversations about people’s wishes and preferences, not just about whether they are resuscitated or not.

- As difficult as these conversations can be, we need to be having them and there are resources available to help you.

Update on available information

Clara gave a significant amount of information on online resources, academic articles, and other useful literature signposting. All of the information is included in her slidedeck.

Clara's slides

Online resources

- Neurocritical Care Society COVID-19 resources:

www.neurocriticalcare.org/resources/covid19 - Swiss Medical Weekly articles:

smw.ch/covid-19 - Covid-19 HSE Clinical Guidance and Evidence:

hse.drsteevenslibrary.ie/Covid19V2 - Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy podcasts and webinars:

www.cidrap.umn.edu/covid-19/podcasts-webinars - Frontiers YouTube channel

- IDEAL Programme’s Coronavirus response – 5 key messages for people living with dementia

Chair

Prof Iracema Leroi

Prof Iracema LeroiProfessor in geriatric psychiatry, Trinity College Dublin & Faculty, GBHI

Speakers

Dr Clara Domínguez Vivero

Dr Clara Domínguez ViveroClinical neurologist, galician health service, pontevedra, Spain, Atlantic Fellow in Equity for Brain Health, GBHI

Dr Joseph Kane

Dr Joseph KaneAcademic clinical lecturer, Queen’s University Belfast

Dr Gregor Russell

Dr Gregor RussellConsultant old age psychiatrist and R&D director, Bradford District Care NHS Foundation Trust

Promoting prevention, supporting management

Led by proactive clinicians determined to see improvement in the way we prevent, diagnose and manage dementias, Dementia Academy supports healthcare professionals with the latest tools, resources and courses to do just that.