Before you watch this webinar

Enhancing your learning experience begins with understanding you better. Collecting data enables us to tailor our educational content specifically for our audience. Discover more about how we handle your information in our Privacy Policy.

Event

Radiologically-isolated syndrome

Our sponsor

Case: A 32-year old neurology trainee is referred to you for an opinion. She has a long history of atypical migraine without any aura. A colleague who saw her as a favour ordered an MRI scan to exclude any intracranial pathology. The MRI has come back abnormal with multiple high-signal white matter lesions typical of demyelination. Two of the lesions, one in the deep white matter of the right parietal lobe and a second juxtacortical lesion in the left frontal lobe, enhanced after gadolinium administration. There is no history of any previous neurological symptoms.

Objective: To review the diagnosis, epidemiology and management of radiologically-isolated syndrome.

Presentation slides

CPD accreditation

'Radiologically-isolated syndrome' has been approved by the Federation of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom for 1 category 1 (external) CPD credit(s). Please note CPD Federation approval does not include satellite symposia sessions.

Summary

Our expert panel held a case-based discussion, chaired by Dr Camilla Blain, to review the diagnosis, epidemiology and management of radiologically-isolated syndrome in multiple sclerosis.

Consultant neuroradiologist Audrey Sinclair and MS nurse specialist and clinical lead Amy Harbour joined consultant neurologist Camilla as they unpicked what to do at the very beginning of someone's neurological journey.

Camilla began the session by discussing the clinical implications of radiologically-isolated syndrome (RIS), looking at what RIS is, how common is it, and what is the likelihood of developing either clinically-isolated syndrome (CIS) or multiple sclerosis (MS) after recieving this diagnosis and how someone with RIS ought to be managed.

Following this, Audrey looked at the radiology involved in this and the potential pitfalls in making this radiological diagnosis. Finally, Amy talked about the implications of receiving this diagnosis for the person in question and how MS nurses can positively input into this.

Camilla presented the case that she used to support her presentation:

- A 32-year old neurology trainee is referred to you for an opinion.

- She has a long history of atypical migraine without any aura.

- A colleague who saw her as a favour ordered an MRI scan to exclude any intracranial pathology.

- The MRI has come back abnormal with multiple high-signal white matter lesions typical of demyelination.

- Two of the lesions, one in the deep white matter of the right parietal lobe and a second juxtacortical lesion in the left frontal lobe, enhanced after gadolinium administration.

- There is no history of any previous neurological symptoms.

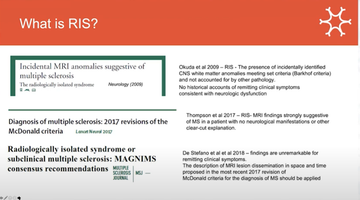

Defining RIS

Camilla used research papers from 2009 through to 2018 to create a firm picture of the clinical definition (fig 1).

'RIS is defined as the presence of incidentally identified CNS ehite matter anomalies meeting set criteria (Barkhof criteria 1997) and not accounted for by another pathology and with no historical accounts of remitting clinical symptoms consistent with neurologic dysfunction.'

Okuda et al 2009

Figure 1: Research papers from 2009 through to 2018 outlining and defining RIS over the past 2 decades to provide a clinical definition

Common occurrence?

RIS is uncommon in comparison to other presentations in clinic - retrospective meta-analysis studies of c15,500 and c2000 people looking at MRI results for reasons other than MS have found the presence of demyelination in 0.06% and 0.05% of cases respectively (Morris 2009; Granberg et al, 2013).

Camilla asked why RIS is not considered prodromal or subclinical MS, presenting the lack of overt clinical evidence for this, and sharing Okuda et al's review of RIS over a 5 year period and the likelihood of further clinical activity (Okuda 2014). Of 451 people presenting with RIS, 34% went on to have a clinical event within a 5 year period, and of these, 9.6% went on to develop primary progressive MS (PPMS) with spinal cord lesion involvement.

A further study looking at people with RIS after 10 years found that 50% had gone on to have a clinical event - meaning, conversely, that almost half had not despite the association of RIS with CIS or MS- and Camilla queried why this might be (Lebrun-Frenay 2020).

She suggested that considering risk factors is important in understanding the likelihood of, or time until, a clinical event in someone with RIS, including age, spinal cord lesion and gadolinium-enhancing lesions, although not oligoclonal bands and cited a prospective study (Lebrun-Frenay 2021).

Practical matters

Discussing the diagnosis of RIS can be challenging - it is something that looks like MS but is not MS, and Camilla noted that, whilst there is a possibility to do more testing, there is also 'the opportunity of not knowing' which can be a positive one.

Camilla outlined four positive actions to take with someone with RIS:

- Provide the person with the number of the MS nurse or the relapse service in the event of a clinical event

- Give clear information on what a clinical event might be and what to look out for

- Establish an annual monitoring appointment for them

- Encourage vitamin D supplementation

Camilla explained that there is no evidence for beginning a disease-modifying treatment as yet although this may be done in the future with a risk stratification algorithm for appropriate individuals. She mentioned current research in this including two clinical trials are being conducted in this for teriflunomide (TERIS: results expected Oct 2022), dimethyl fumerate (ARISE: results were expected in March this year) and a research trial in Ocrelizumab (results expected 2028).

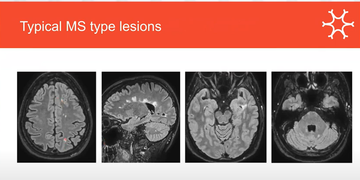

Location, location, location

Consultant neuroradiologist Dr Audrey Sinclair opened her presentation by asking what makes RIS the diagnosis, and harkened back to Camilla's comments on the Okuda criteria (2009) and mentioned the modified McDonald diagnostic criteria (2017).

'White matter lesions are a common finding, and increase in prevalence with age. The term 'non-specific white matter hyperintensities' is used in abundance by radiologists - and certainly by me - so what constitutes RIS?'

Dr Audrey Sinclair

The modified MAGNIMS consensus (de Stefano 2018) excludes white matter lesions caused by other diseases and there is a caution to radiologists in the criteria regarding older patients because of the increased likelihood of white matter lesions with age.

Audrey shared that the location of white matter lesions is essential in deciding if they are indicative of RIS. In older patients, looking for a number of periventricular lesions is helpful as these are where age-related lesions often are, with Audrey terming them 'brain wrinkles'. Occasionally Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) may cause lesions in the juxtacortical regions, but generally lesions located in the following areas are most indicative of RIS or multiple sclerosis (MS) (fig 2):

- juxtacortical / cortical

- callosal

- peritrigonal

- around temporal horns

Figure 2: MRI scans demonstrating white matter lesions in areas indicative of MS or RIS:

Other signs that the lesion is indicative of demyelination include:

- larger (3mm or larger)

- ovoid in shape

- perivenular (located around a central vein)

- paramagnetic rim sign (Suthiphosuwan 2020) (requires a 3 Tesla MRI scanner and a specific sequence; is indicative of greater disability being likely)

Narrow it down

'An important part of the diagnosis of RIS is making sure you exclude other diagnoses, particularly small vessel disease.'

Dr Audrey Sinclair

As well as small vessel disease (leukoaraiosis) Audrey outlined other conditions that need excluding to have a certain diagnosis of RIS and highlighted how these might be identified by showing various MRI scans and discussing these, including:

- migraine

- Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)

- neuroinflammatory conditions such as sarcoidosis and Bechets.

Audrey then used a case study of a 59 year old female and her MRI scans to demonstrate possible RIS, and went on to highlight the risk markers for subsequent clinical events, reiterating Camilla's earlier points about spinal cord lesions being more likely to lead to a clinical event, and gadolinium-enhanced lesions on follow-up being indicative of later developing relapsing-remitting MS.

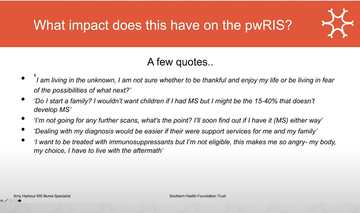

What does it mean to get a diagnosis of RIS?

Amy Harbour, MS specialist nurse and clinical lead, then shared the impact of a diagnosis of RIS on an individual, and the role of the MS specialist nurse in supporting these people.

Beginning by considering what support is available to people who receive a diagnosis of RIS, Amy shared that a 'quick Google' will bring up both the MS Trust and the MS Society, but neither have a great deal of information on RIS at present. Neurologists are often able to provide information to people on the data and statistics around RIS and GPs may be able to help, however, this is a reasonably new diagnosis (Okuda 2009) and they may have limited understanding of RIS and its implications. Referral to the MS nurse may or may not be the best option for support.

Amy shared a number of quotes from individuals who have had a diagnosis of RIS with a huge range of emotions and responses to the diagnosis (fig 3).

Figure 3: Individual's response to a diagnosis of RIS is varied and emotive

Are MS nurses best placed for support?

Amy suggested that newer nurses coming into post have a great deal more training around disease-modifying therapies, blood monitoring and that there is more information required on supporting other aspects of care, including RIS.

With limited guidance on how to manage a person with RIS, the regularity and method of monitoring is very much dependent on area, Amy shared, with some areas establishing routine follow up and others opting for a patient-led approach.

That lack of guidance impacts other elements of support for someone with RIS as well, including around family planning. Amy advised offering discussions around family planning with someone with RIS in the same way as with a newly diagnosed patient with MS, considering all the risks and management strategies, and supporting them to make their best decision.

Amy questioned capacity regarding nurse caseloads, and was clear that adding another cohort of individuals requiring support into specialist nurse remit will have an implication. She also posed questions around longevity of follow-ups without a further clinical event, and suggested guidance on this would be welcome.

Amy also highlighted that whether supporting someone with RIS is included as part of a nurses' job specification - and therefore reflected in their pay - and thought that this may, again, vary from area to area.

Common questions from someone with RIS

Amy shared a number of questions that she is commonly asked in clinic by people who have received a diagnosis of RIS and gave her responses:

- Do I need to inform the DVLA of my diagnosis? (Yes)

- Do I need to inform my driving insurance? (Yes)

- Can I claim critical illness? (Not on RIS alone)

- Can I claim PIP? (Not on RIS alone)

- Shall I tell my employer? (Personal choice)

Amy went on to question how to support people with RIS within current practice, suggesting both pros and cons. She highlighted that early education leads to empowerment, but there is not a clear way to do this, although offering appointments to discuss concerns, anxieties and perhaps refer on to counselling if needed might be a positive way forward.

Amy asked rhetorical questions including whether people with RIS ought to attend newly diagnosed days so that they understand what to look out for in the event of experiencing a relapse, whether to offer them a 'recently diagnosed' pack - or whether something separate is required, or even needs to be provided at a national level.

Amy encouraged sharing best practice and asked for anyone with current practice or a pathway supporting RIS to share their thoughts and experiences (please email Neurology Academy and we will add information to this page).

Podcast

Our Multiple Sclerosis webinars are available on SoundCloud:

soundcloud.com/neurologyacademy

Our sponsor

Encouraging excellence, developing leaders, inspiring change

MS Academy was established in 2016 and in that time has accomplished a huge amount with exciting feedback demonstrating delegates feel inspired and energised along their personal and service development journeys. The various different levels of specialist MS training we offer are dedicated to case-based learning and practical application of cutting edge research.