Dilemma and deliberation of ethics in Parkinson's care: Parkinson's Cutting Edge Science conference 2022

Event reportsOur Parkinson's Cutting Edge Science conference this year, chaired by Dr Emily Henderson, was attended by over 170 Parkinson's specialists spanning Neurology, Old age psychiatry, and Medicine for the elderly, with nurses, therapists and consultants discussing and debating nuanced aspects of Parkinson's treatment, management and care. Each week, we will take a closer look at one of the brilliant sessions.

Dr Robin Fackrell, Medicine for the elderly consultant, delved into the 'dilemma and deliberation' of ethics in Parkinson's care, opting for a more interactive format with discussion and questions throughout the presentation.

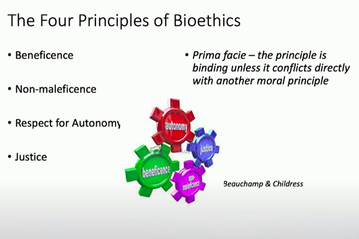

He set the scene with the four principles of bioethics:

In discussing each of these, Robin summarised these four bioethics are:

- Beneficence: acting to promote a good outcome

- Non-maleficence: promoting the concept of 'do no harm'

- Justice: the principle of egalitarian care - all people should be treated fairly

- Autonomy: trumps all these, generally.

When he noted that autonomy generally trumps the other elements, this spurred early debate from the floor of what principles trump, how to balance them out when different professionals involved in care may have different perspectives, and how to acknowledge individuals' rights, preferences and autonomy at all times.

Then, using case studies, Robin encouraged people to 'park their preconceptions', and led discussion around complex scenarios where legal obligations and perceived risks to the individual or others around them may need consideration. He opened these discussions with the caveat that, in many situations, there is not one 'correct' way to proceed but a thoughtful weighing up of factors and a personal choice to take action.

Case study 1:

A homosexual gentleman who was a headmaster at a prestigious boy's school and lives with Parkinson's, takes ropinirole and COMT inhibitors to manage quite pronounced 'off' periods with both motor and non-motor symptoms. He is a private and independent man, lives alone, and insists that no-one else knows of his diagnosis at his school. He has said he is accessing pornography and has been cruising for sex.

Conversations as to whether this is his baseline behaviour or a new behaviour, questions as to safeguarding or legal issues given his role as a headteacher versus patient/physician confidentiality, and perceived risks were all discussed around the room. Did raising his use of pornography imply that he felt there was a problem, or would he have avoided discussing it if he felt it was a problem?

Robin discussed his approach in this case, noting how he had to look outside of his own concerns and preconceptions. After careful review, there was no paraphilia, no evidence of impulse-control disorder, and these behaviours preceded his diagnosis; there was no need to do anything further in this case.

Case study 2:

An older gentleman in his 70's is still a practising farmer and drives a tractor regularly in local areas. He takes co-careldopa, rotigotine and rasagiline. Following a fall outside a local pub, a constable called the Medicine for the Elderly department to express concern over his continuing to drive the tractor. He has freezing on gait initiation and difficulty turning, a 22/30 on his mini-ACE (but no baseline to review this against) and says he has never had an alcoholic drink or a road traffic accident.

Robin explained that his mental capacity was found to be fine and a driving test in a tractor proved successful. Robin noted that the gentleman left school at 12 and that his ACE score would probably never have been a high one - his family had not noticed any changes in his cognition and he was very good at his job as a farmer. It transpired that he had tripped on a curbstone outside the pub, not having been inside.

Case study 3:

A 39 year old lady going through IVF with a new partner who is concerned that may pass on Parkinson's to her child and is considering an egg donor. Her Obs-Gyn team seem unaware of her diagnosis. She is taking ropinirole, co-beneldopa and rasagiline.

Initial concerns were around the safety of these drugs in pregnancy; Robin noted that rasagiline and ropinirole were probably best avoided. Referring to someone who specialises in neurogenetics for advice was suggested from the floor.

Robin queried whether this was a rash or impulse decision with her new partner. There were queries about why the ObsGyn team did not know about Parkinson's, and whether the partner knew of the diagnosis. Robin asked if there were obligations to the future child and their future care - but there are no legal obligations here.

After exploring, Robin chose to have long discussions with herself and invited her partner. It transpired that her partner had been a friend for some time and was aware of her condition. She had wanted a child for some time and had had IVF in the past. She had chosen not to mention it to her ObsGyn team as she was concerned it may influence their decision to support her in the treatment. However, after having these discussions she decided not to go ahead with the IVF as she felt it would not be fair on her future child.

Case study 4:

A 62 year old high-court judge with a very minimal support network diagnosed via a private appointment as having idiopathic Parkinson's disease, and has not told anyone of his diagnosis. He was concerned with poor sleep, reduced concentration and a reduction in his self-reported executive function. He had a mini-ACE of 27/30. He also then noted hallucinatory visual disturbances and threatened legal action should his physician mention these symptoms to anyone. He had been prescribed selegiline by his private physician.

Comments from the floor included a concern over his ACE score given his professional role, and that in the context, this was probably low for his cognitive abilities. The room suggested that he may not have IPD but that there may be a differential such as Lewy body dementia.

Robin highlighted the concerns facing a physician who is being threatened by legal action, and without the job title would there be an obligation to highlight this? Is there a justice issue there? However there is an obligation to express concerns to the patient. Robin explained that he stopped the selegiline and rediagnosing him with LBD, and encouraged his access to a support network. Together they also consulted the BAR council for advice. Robin noted that, had the individual refused all input, he may have had to act in his, and others' best interests against his wishes.

Case study 5:

A lady of 74 who had been treated for Parkinson's for 18 years under a different physician. She had been admitted to hospital with urosepsis, delirium and an absent swallow. She had had marked swallowing difficulties over the past weeks but had otherwise been 'doing well'. She was unable to advocate for herself, and had no advance care plan or Lasting power of attorney in place. Her husband and son were diametrically opposed in their views with the husband wanting to preserve life at all costs and the son believing her quality of life to now be insufficient to promote life further.

Two comments from the floor felt that urosepsis should be treated with the hope that her swallow returns and also more information could be gathered. If she was doing well before the swallowing was compromised she seemed to have a good quality of life. Another suggestion was a 'halfway house' of assisted feeding without PEG in the short term to see if she can recover.

Robin reminded everyone that, without the autonomy to consider, non-maleficence and beneficence have to be prioritised.

After discussing what the interventions like PEG would entail with the husband, and highlighting that quality of life rather than prolonged life, was the priority. The interventions were stopped and the lady passed away with supportive palliative care and in relative comfort.

In closing

Finally Robin opened up discussion around noticing Parkinson's symptoms in a colleague or friend and whether it is appropriate to approach the colleague and have this conversation with them. He noted that this is more a moral decision than an ethical one and comments from the floor were wide-ranging. They included that unsolicited diagnoses from friends can be damaging because noticing the symptoms in oneself is part of the acceptance element around a diagnosis. Others felt that the individual may already be being treated under a different hospital, whilst another pointed out that it is a personal moral choice - 'does it keep you awake at night?' - and if it does, that 'a quiet coffee' might be the answer, however uncomfortable that seems.

Ultimately, Robin's session highlighted the difficulty and nuance involved in ethical decisions and the importance of coming to them for that individual, and without any bias or agenda, each time one emerges.

This meeting is designed and delivered by the Parkinson’s Academy and sponsored by BIAL Pharma. The sponsor has had no input into the educational content of this meeting.

Related articles

'The things you can't get from the books'

Parkinson's Academy, our original and longest running Academy, houses 23 years of inspirational projects, resources, and evidence for improving outcomes for people with Parkinson's. The Academy has a truly collegiate feel and prides itself on delivering 'the things you can't get from books' - a practical learning model which inspires all Neurology Academy courses.