How do dementia, psychosis and Parkinson’s disease overlap with each other?

Event reportsBack in June the Parkinson’s Academy hosted “Cutting Edge Science for Parkinson’s Clinicians”, an educational meeting sponsored by Bial Pharma. Now in its second year the meeting was a sell-out again and expectations were high. Chaired by Dr Peter Fletcher (Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust), the meeting was designed to cater to the diverse needs and interests of its varied audience of neurologists, care of the elderly physicians, psychiatrists and Parkinson’s nurses.

This year, the meeting’s theme was to ‘Question everything’, to review what we already know, and to think about how clinical observations and cross-team collaborations can drive us forward. Each week we are posting an article to look at the meeting’s speaker sessions in more detail.

Prof Iracema Leroi

Professor in geriatric psychiatry, Trinity College Dublin & Faculty, GBHI

Opened Professor Iracema Leroi (Trinity College, Dublin). Neuropsychiatric symptoms in PD include dementia, psychosis, depression, anxiety, apathy and impulse control disorders, and affect >80% of people living with PD. Professor Leroi noted that the disease is now often more accurately described as a neuropsychiatric disorder.1

The lifetime prevalence of psychosis in PD is over 50%, but increases to about 70% in patients with dementia, and the spectrum of psychotic symptoms in PD ranges widely, from mild visual illusions to fully formed hallucinations and delusions. Hallucinations occur more frequently during times of decreased environmental stimulation, such as in the evening, and while auditory, olfactory or tactile hallucinations are less common, they do occur, with up to 20% of PD patients reporting auditory hallucinations. Delusions in PD are less common than hallucinations and are usually paranoid or jealous in character and focus on a single theme, such as spousal infidelity. While the causes of psychosis in PD are complex, Professor Leroi discussed how suffers are likely to have a certain susceptibility risk profile and impaired coping skills. When dopaminergic medications are added to the mix, they act as a ‘susceptibility multiplier’ and psychoses become manifest.

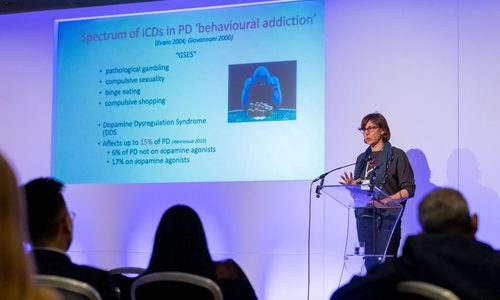

Compared with other neuropsychiatric symptoms in PD, apathy, a state of indifference, characterised by a lack of emotion, motivation or interest, has, to date, received scant attention. However, apathy occurs in at least 40% of PD patients and can occur independently of depression and cognitive impairment, although overlap is common. It is now considered to be on the spectrum of motivational problems of PD, which range from apathy to impulse control disorders. Diagnosis can be tricky in people with PD, particularly as people with feelings of apathy tend not to complain. Indeed, it is often family and carers who act and seek help because the patient is “Not interested in interacting”. Apathy is thought to reflect a blunted response in a person’s reward system, and it is more likely to be a consequence of underlying disease progression than a psychological reaction or adaptation to disability. Professor Leroi advised that clinicians need to be aware that apathy need not always be a focus for intervention – sometimes a discussion is all that’s needed.2 When appropriate, treatment should start with optimizing dopamine replacement therapy, and, if this is not sufficient, a SSRI can be considered. Professor Leroi added that high levels of apathy are strongly predictive of negative cognitive and behavioural outcomes over time, suggesting that apathy may be a behavioural marker of early cognitive decline.

Psychosis and dementia frequently co-exist, and the development of one symptom often heralds the advent of the other.3 Psychosis and dementia are associated with poorer quality of life, increased morbidity and mortality, and increased caregiver burden and nursing home placement.4 Clinical risk factors for cognitive impairment in PD include: older age, older age at disease onset, akinetic-rigid forms, increased disease severity and longer duration of motor symptoms. Professor Leroi noted that there is growing interest in non-pharmacological treatments for cognitive impairment in PD. Non-medication based treatments for PD dementia and PD-MCI include mindfulness, cognitive training, physical exercise, music and art therapy. One theory behind the use of cognitive therapy is the promotion of cognitive reserve in order to prevent or delay onset of cognitive impairment, as well as to slow progression once impairment is already present. Cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) is an evidence-based psychosocial intervention that involves engaging and cognitively stimulating activities and discussions based on principles of errorless learning and validation. While it is often a group-based program, Professor Leroi described the INVEST study, which uses an individualized form specifically for people with parkinsonian syndromes to be delivered by their care partners at home (PD-CST).5 PD-CST sessions are prompted by a manual and usually involve a new themed cognitive activity (word game, categorising objects, debate etc). This protocol is now ready for a randomized controlled clinical trial.

References:

- Weintraub D, Burn DJ. Parkinson's disease: the quintessential neuropsychiatric disorder. Mov Disord 2011;26(6):1022-1031.

- Simpson J, McMillan H, Leroi I, Murray CD. Experiences of apathy in people with Parkinson's disease: a qualitative exploration. Disabil Rehabil 2015;37(7):611-619.

- Ffytche DH, Pereira JB, Ballard C, Chaudhuri KR, Weintraub D, Aarsland D. Risk factors for early psychosis in PD: insights from the Parkinson's Progression Markers Initiative. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017;88(4):325-331.

- Goldman JG, Holden S. Treatment of psychosis and dementia in Parkinson's disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2014;16(3):281.

- McCormick SA, Vatter S, Carter LA, et al. Parkinson's-adapted cognitive stimulation therapy: feasibility and acceptability in Lewy body spectrum disorders. J Neurol 2019;266(7):1756-1770

This meeting was designed and delivered by the Parkinson’s Academy and sponsored by Bial Pharma. The sponsor has had no input into the educational content or organisation of this meeting.

Related articles

'The things you can't get from the books'

Parkinson's Academy, our original and longest running Academy, houses 23 years of inspirational projects, resources, and evidence for improving outcomes for people with Parkinson's. The Academy has a truly collegiate feel and prides itself on delivering 'the things you can't get from books' - a practical learning model which inspires all Neurology Academy courses.