Is exercise an integral part of Parkinson's management?

Event reportsOur Parkinson's Cutting Edge Science conference took place on 21st June 2023 at Birmingham Conference and Events Centre and was chaired by Prof Emily Henderson.

You can read an overview of the entire event here.

This write up is one of a series covering each session in detail for those who were unable to attend, or want to reflect on what they heard.

The event was sponsored by Bial Pharma. The sponsor had no input into the educational content of the meeting.

Is exercise an integral part of Parkinson's management?

In her extremely well-received session, Dr Julie Jones began by reviewing the importance of exercise for people with Parkinson's. Noting that more studies were published in 2022 than in the decade between 2000-2010 and that there are now 70 systematic reviews across exercise, she highlighted the growing interest in, and evidence-base for, exercise and physical activity in Parkinson's. Throughout her talk, Julie reviewed the evidence and suggested the barriers to implementation and the wider considerations needed to put this evidence into practice.

Fig 1: Julie's slide summarising why there is an interest in exercise for people with Parkinson's

Aerobic activity

Looking at the Park-in-Shape study (van der Kolk 2019; Johansson 2021) and the SPARX11 study (Moore 2013) Julie highlighted that whilst there are a lot of benefits to these studies, there are limitations to their application into real life. For example, whilst they both found significant improvement in people's motor function (Park-inShape found a 4 point improvement on the UPRS scale), the level of strenuous exercise which produced the benefits in the Park-in-Shape study is not accessible for everyone living with Parkinson's, whilst thrice-weekly treadmill training as examined in the SPARX11 study might not be enjoyable or accessible to everyone living with Parkinson's. Equally, whilst the treadmill training was found to improve motor function, it did not positively affect gait, and whilst it improved aerobic health, perhaps would not support the muscle development needed to sustain that motor function like strength training would. Julie therefore encouraged professionals to be mindful in seeing each benefit as one aspect of an overall exercise puzzle piece.

Strength training

Moving to the meta-analyses and systematic reviews for strength training for building muscle, improving bone health and increasing strength (Tillman 2015; Gollan 2022), Julie highlighted that people with Parkinson's can gain muscle strength as well as another person their age without Parkinson's, and that there are significant gains to be had when a strength programme is followed for more than 8 weeks.

However, she also noted again that there are real limitations in these studies if they are applied in isolation - in translating the strength increase in one muscle group to function across a whole movement. For example, Julie explained, bicep curls will build biceps in people with Parkinson's, but applying this to everyday life, carrying a shopping bag requires the whole arm including wrist and grip strength, as well as core strength and balance, so taking a person's goal into account is essential.

'The take home message here is: if you want your patients to get stronger, give them strength exercises, but if their goal is to improve their walking, we might need to give some gait re-education as well, rather than just a strength programme.'

Balance

Studies in balance have again been found positive yet those which take a more dynamic approach to this, combining balance exercises with functional tasks, gait education and such have a better outcome (Yitayeh & Teshome 2015). Regularity, consistency, and moving multiple parts of the body to achieve an outcome all need consideration when applying these studies to clinical practice. When training for balance, Julie is clear that balance has to be challenged and doing this with confidence and safety can be difficult. She uses the example of balance to navigate a cluttered environment like a garden centre, sharing that balance in this circumstance requires a cognitive component and swift responsiveness, not only the ability to stand on one leg.

'A lot of work is needed in the Parkinson's community to build self-efficacy and self-confidence. That's a real challenge in our services, because the way to do that is to give people time and have a supervised approach to exercise. When we're left unsupervised, do we tend to 'do' the exercise?

Intensity is important - people need to be seen regularly to develop that habit… and so is supervision. If you know Julie the Physio is coming to your house to check you're doing your exercises, you're probably going to do them!'

Gait

In reviewing evidence around exercise and gait, Julie explained that in a meta-analysis of 159 studies encompassing 24 approaches to exercise, those which had a specific training programme for gait had more impact. 'If we want people to get better at walking, we need to give them walking practice', she said, and discussed her own approaches to walking practice, from obstacle courses to supported body-weight treadmill training and the use of tech which reflects their gait back to them.

Fig 2: Julie's 'What can be learned from research' slide

'People with Parkinson's have many problems that can benefit from exercise, so there's no one form of exercise that's deemed superior… because of the varied problems they have, they need a varied exercise programme.'

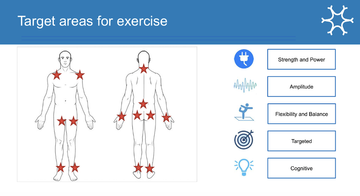

Julie was clear that a programme needs to have a strength, balance and aerobic component, and that mixing different exercises together which will meet the individual needs of that person is essential. For example, tai chi may help with balance, muscle control and anxiety but is unlikely to improve gait patterns or a person's ability to suddenly stop. She also explained that group activities can be beneficial with community and shared experience significantly motivating people, providing a safe space where they can feel understood.

She explained that exercise supports wider health and wellbeing, increasing quality of life, providing a sense of control and agency and offering wider health benefits including promoting brain health and reducing comorbidities - and shared comments and experiences from some of the people with Parkinson's that she supports to depict this.

Take-home messages about exercise in Parkinson's

- Varied physical activities are needed with strength, balance and aerobic elements

- Habit formation is key - it needs to be regular to be impactful

- Supervision is needed; there needs to be a consistency and a sense of accountability around doing the exercises

- Less than 30 minutes is not considered as efficacious, and building up to this, ensuring confidence and enjoyment is important

- We need to target needs - what are their weaknesses or needs and what exercise could target it?

- Group-based exercise for people with Parkinson's

- Exercise supports wider health and wellbeing, increasing quality of life, providing a sense of control and agency and offering wider health benefits including promoting brain health and reducing comorbidities

Exercise as a disease-modifier

The potential role of exercise as a disease-modifier is becoming clearer across motor and cognitive function, mood and quality of life with improved results compared to non-exercisers after one year (Oguh 2014; Paul 2019), a slower rate of decline in motor and quality of life outcomes over two years (Rafferty 2017) and slower progression of motor and non-motor symptoms generally (Amara 2019).

There are also potential mechanisms for neuro-modification through exercise, including promotion of neuroplasticity, creation of new neurons,increased transmission of dopamine, and reduction of mitochondria dysfunction and alpha-synuclein expression.However, there is not yet robust evidence that exercise does have a disease-modifying effect -and there need to be more studies in this.

Combating sedentarism

Despite all this evidence, however, 70% of people with Parkinson's are sedentary (Lord et al 2013) and physical activity levels reduce from diagnosis onwards (Cavanagh 2015). Julie shared that the proportion of falls in people with Parkinson's not only comes from the condition, but from their sedentarism. Additionally, changes with gait also impact activity and falls, and within the early years living with Parkinson's gait dysfunction occurs in most people regardless of the dopaminergic therapy they may be on. Exercise and gait correction can help with this.

Resources to share with your patients

- Parkinson's UK 'Stay active at home' exercise videos via YouTube

- Reach your peak online exercise community for people with Parkinson's

- Neuro heroes physio-led online exercise space

- Parkinson's Active from Parkinson's UK

Questions from the floor

When asked how we encourage the 70% of people with Parkinson's who are sedentary, Julie encourages a slow and steady approach, beginning with short walks between lampposts and walking as quickly as possible.

In response to a question about the benefits of nordic walking, Julie confirmed that this has a good evidence-base.

Considering apathetic patients, Julie recommended finding a form of physical activity that they can enjoy and / or which is small, and to encourage them to monitor themselves. These might be activities such as climbing stairs, playing darts, gardening, and so on.

Related articles

'The things you can't get from the books'

Parkinson's Academy, our original and longest running Academy, houses 23 years of inspirational projects, resources, and evidence for improving outcomes for people with Parkinson's. The Academy has a truly collegiate feel and prides itself on delivering 'the things you can't get from books' - a practical learning model which inspires all Neurology Academy courses.