‘The forgotten ones?’ – Surveying our current practice with respect to care home residents with Parkinson’s disease

Background

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative condition impacting significantly on the functioning of patients both through its motor and non-motor features. As the disease progresses many patients through functional and cognitive decline may require care home placement to meet their on-going care needs.¹ These individuals with usually advanced disease are often more challenging to follow-up and are at risk of sub-optimal care, exposed to the risk of emergency hospital admissions and subsequent prolonged hospital stay as a result of the complications of their disease.²

Parkinson’s disease patients in care homes hence represent a particular frail cohort of patients with on-going symptomatic needs and hence the aim of this project is to examine the current practice from the movement disorder team in County Durham and Darlington in following up these patients.

County Durham and Darlington Foundation Trust movement disorder services follows up a population of approximately 1200 patients with various movement disorders the majority which have Parkinson’s disease and hence they are likely to have a proportion of their patients in care homes. As although these patients may derive less benefit from conventional motor therapies for Parkinson’s disease as their disease progresses they may benefit significantly from interventions such as advanced care planning and symptomatic support of their symptoms.³

Method

We examined the County Durham and Darlington Parkinson’s disease database which records all patient’s residences, diagnosis and patient contacts including clinic and telephone advice. We sampled a patient cohort of Parkinson’s disease patients in care homes identified from this (residential and nursing home). We subsequently examined the notes retrospectively and the trusts electronic records to identify the following factors:-

- Demographics

- Diagnosis

- Movement disorder team patient input from June 2014 to 2015

- Seen in clinic by consultant or nurse specialist

- Telephone contact

- Community visit and review

- Symptomatic burden as described in clinic letters

- Unplanned acute admissions

- Any record of anticipatory care planning

Only patients with a diagnosis of a Parkinsonian disorder were included with patients with drug-induced tremor, essential tremor and other tremor diagnoses excluded.

We also sampled a number of patients who lived in their own home, to appreciate and approximate the normal service contact a patient has for comparison. Hence appreciate if there is a suggestion of a discrepancy in the contact with the movement disorder services locally that care home patients receive.

Results

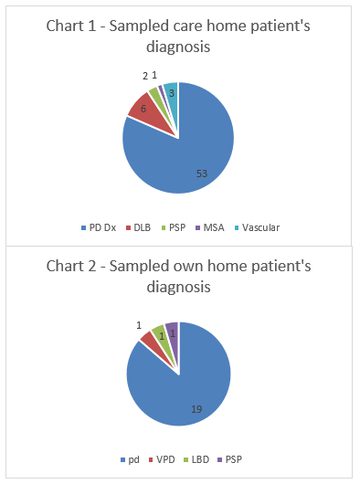

The database identified 1238 patients followed up by the movement disorder services. Of these patients 150 resided in care homes. Sixty-five patients with and average age of 81.1 years were sampled from this population with a variety of diagnoses, the majority (82%) of which were Parkinson’s disease (Chart 1). We subsequently randomly sampled 22 patients, average age 78.2 years who lived in their own home with a similar Parkinson’s disease prevalence as shown seen in chart 2.

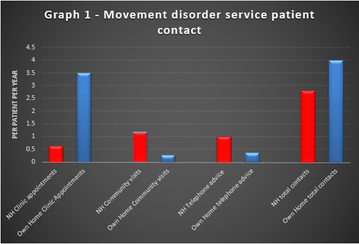

The care home patients generated 41 clinic appointments in the previous year, equating to 0.63 appointments per patient per year. They received 65 telephone advice calls and had 76 community visits by Parkinson disease nurse specialists (1.17 visits per patient per year). The sample of non-care home patients had attended 3.5 clinic appointments per patient per year, with 0.27 community visits per patient and 0.36 telephone advice calls per patient per year. (See Graph 1)

From the nursing home patient cohort, 32 patients were admitted in the past year amassing a total of 57 acute admissions in these 65 patients (0.88 admissions/patient). This compared to the 4 admissions (0.18 admissions per patient) in those patients who lived in their own home. Examining the letters from the past year only one care home patient had documented evidence of anticipatory care planning in the context of their advanced disease.

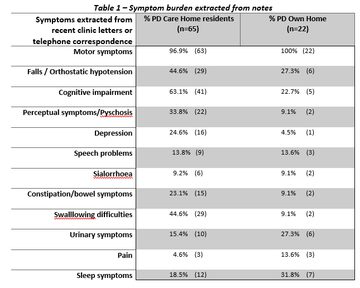

The symptoms described in the patient’s documentation for the past year in the care home residents and patients in their own home is summarised in Table 1. The care home residents had significantly more documented problems with cognitive impairment, falls, perceptual symptoms, constipation and swallowing difficulties.

Discussion

A significant proportion of patients within the service reside in care homes and hence this needs consideration. Although the sample size varied between the groups some themes are apparent from the data extracted. This clearly needs interpreted in the context of marked limitations in the data extracted from the database, clinical notes and clinic letters. There is a likely underestimate in patient symptomatic burden and a reliance on the accuracy of assessment and the subsequent letter, in reflecting the patient’s symptoms. Despite this there is still marked symptomatic burden identified in the care home resident population suggesting that these patients have on-going needs which may benefit from specialist input as one might expect.

Although the service supports them with increased telephone advice and community visits from the Parkinson disease specialist nurse, they have low rates of clinic attendance and hence consultant input. It can be challenging to get these patients to clinic given their marked symptomatic burden and hence thought needs to be given for alternate strategies. Currently overall, these patients with advanced disease appear to have lower incidences of specialist clinical contact. Interestingly these patients appear to have a high rate of acute admissions compared to those in their own home and this perhaps is not helped by the lack of anticipatory care planning in the sample we examined. There is hence a potential opportunity to highlight these patients as those who we should be thinking about symptomatic needs and future care planning to avoid complications and prevent avoidable admissions.

This data helps to describe and add weight to the on-going problems that patients in care homes suffer in County Durham and Darlington. Strategies need considering of how best to support these patients, ensuring time and expertise is in place to focus on areas such as anticipatory care planning which is an unmet need in our patient cohort. This is an area currently being targeted in elderly care within the trust through the piloting of projects on emergency care planning using Deciding Right documentation.4 However, this perhaps needs to be more proactive as increasing input into care homes for this purpose may improve patient symptoms and the avoidance of future complications, but further work in this area is needed.

Limitations

- Sample sizes not equivalent between cohorts due to time constraints

- Relies on retrospective analysis of notes and letters

- Relies on all patient contact being logged in the notes, electronic patient database or the trust’s electronic records

- Likely underestimate of symptoms documented in letters compared to those actually experienced

- The unplanned admissions only take into account those that occurred with the trust therefore may also be an underestimate

- No analysis of GP databases to evaluate if any primary care anticipatory planning in place or the extent of primary care input with these patients

References

- Aarsland D, Larsen JP, Tandberg E, Laake K. Predictors of Nursing Home Placement in Parkinson’s Disease: A Population-Based, Prospective Study. See comment in PubMed Commons belowJ Am Geriatr Soc. 2000 Aug;48(8): p938-942

- Walker RW, Palmer J, Stancliffe J, et al. Experience of care home residents with Parkinson’s disease: Reason for admission and service use. Geriatrics & Gerontology International 2014; 14 issue 4:p947-953

- Walker RW, Churm D, Dewhurst F et al. Palliative care in people with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease who die in hospital. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014; 4 (1): p64-67

- North East Strategic Clinical Networks (internet) “Deciding Right. An integrated approach to making care decisions in advance with children, young people and adults.“ 2012 (cited 7th April 2015) Available at www.nescn.nhs.uk

More Parkinson's Academy Elderly care Projects

'The things you can't get from the books'

Parkinson's Academy, our original and longest running Academy, houses 23 years of inspirational projects, resources, and evidence for improving outcomes for people with Parkinson's. The Academy has a truly collegiate feel and prides itself on delivering 'the things you can't get from books' - a practical learning model which inspires all Neurology Academy courses.