Opicapone: The promise of the theory

Event reportsBack in June the Parkinson’s Academy hosted “Cutting Edge Science for Parkinson’s Clinicians”, an educational meeting sponsored by Bial Pharma. Now in its second year the meeting was a sell-out again and expectations were high. Chaired by Dr Peter Fletcher(Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust), the meeting was designed to cater to the diverse needs and interests of its varied audience of neurologists, care of the elderly physicians, psychiatrists and Parkinson’s nurses.

This year, the meeting’s theme was to ‘Question everything’, to review what we already know, and to think about how clinical observations and cross-team collaborations can drive us forward. Each week we are posting an article to look at the meeting’s speaker sessions in more detail.

Dr Camille Carroll

Associate professor & consultant neurologist, University of Plymouth Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry

Parkinson’s disease clinicians are increasingly looking towards personalised medicine, where an understanding of phenotypic subtypes guides treatment decisions, but how to reconcile this move with the introduction of new drugs such as opicapone which have been developed for all patients treated with levodopa and experiencing wearing-off fluctuations? Can a drug be used for different reasons? Dr Camille Carroll (University of Plymouth) set out to explore this thought provoking question using the COMT inhibitor opicapone as her case study.

The idea of subtyping in PD is gaining traction in a community who have long recognised the prognostic differences between patients with a predominantly tremulous parkinsonism vs. those with postural instability and gait disorders (and often many non-motor symptoms).1 However, experts such as Professor Ray Chaudhuri are starting to advocate for a move to precision medicine, based on genomic subtypes.2 One interesting avenue of research is homocysteine.

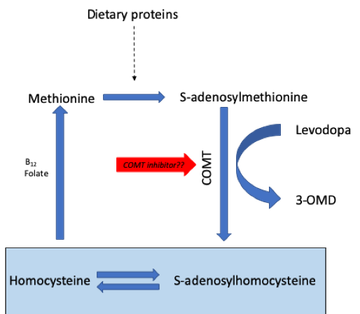

Epidemiological evidence has clearly linked elevation of serum homocysteine to an increased risk of coronary artery disease, stroke, and dementia, and there is long-standing evidence of elevated homocysteine levels in people with PD.3 In PD, administration of levodopa drives up homocysteine levels via the COMT pathway,4 and recent data using serum samples from the DATATOP study suggest those with higher homocysteine levels show worse outcomes in terms of mood and cognition.5 Other studies in PD patients have shown that polymorphisms in the C677T methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene are related to plasma homocysteine concentration, with TT genotypes having much higher plasma levels compared with CC and CT genotypes.6

Vitamin B status is another important factor in modulating homocysteine levels, and one study showed that vitamin B supplementation, but not entacapone, resulted in a decrease in homocysteine compared to placebo.30 However, the study did not consider the combination of both treatments together, was not enriched for TT genotypes (the subgroup who may benefit the most) and was too short to be able to show any impacts on cognition or mood. Since opicapone has been shown to be superior to entacapone in terms of COMT activity (and in reducing 3-OMD levels, which is associated with increased homocysteine),8 Dr Carroll postulated that it may be time to revisit the homocysteine story and evaluate how it may play into the ideas of precision medicine in PD. For example, should patients with the TT polymorphism be proactively treated with opicapone? Controlled trials would be needed to address this question. Closing her presentation, Dr Carroll suggested that it may be important to check homocysteine and vitamin B levels in all PD patients – particularly if they are a high cardiovascular risk. This may be even more important in patients on levodopa infusion therapies where peripheral neuropathy is prevalent and is associated with increased homocysteine as well as reduced vitamins B6 and B12.9 Given that low B12 can improve with vitamin supplementation, future studies should test whether prevention, or early correction, slows development of disability. The potential of using COMT inhibitors, such as opicapone, to reduce homocysteine levels when given with all the new formulations of levodopa now reaching the market remains an unanswered question.

References:

- Selikhova M, Williams DR, Kempster PA, Holton JL, Revesz T, Lees AJ. A clinico-pathological study of subtypes in Parkinson's disease. Brain 2009;132(Pt 11):2947-2957.

- Titova N, Chaudhuri KR. Personalized medicine in Parkinson's disease: Time to be precise. Mov Disord 2017;32(8):1147-1154.

- Postuma RB, Lang AE. Homocysteine and levodopa: should Parkinson disease patients receive preventative therapy? Neurology 2004;63(5):886-891.

- Hu XW, Qin SM, Li D, Hu LF, Liu CF. Elevated homocysteine levels in levodopa-treated idiopathic Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis. Acta Neurol Scand 2013;128(2):73-82.

- Christine CW, Auinger P, Joslin A, Yelpaala Y, Green R, Parkinson Study Group DI. Vitamin B12 and Homocysteine Levels Predict Different Outcomes in Early Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord 2018;33(5):762-770.

- Yasui K, Nakaso K, Kowa H, Takeshima T, Nakashima K. Levodopa-induced hyperhomocysteinaemia in Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand 2003;108(1):66-67.

- Postuma RB, Espay AJ, Zadikoff C, et al. Vitamins and entacapone in levodopa-induced hyperhomocysteinemia: a randomized controlled study. Neurology 2006;66(12):1941-1943.

- Rocha JF, Falcao A, Santos A, et al. Effect of opicapone and entacapone upon levodopa pharmacokinetics during three daily levodopa administrations. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2014;70(9):1059-1071.

- Romagnolo A, Merola A, Artusi CA, Rizzone MG, Zibetti M, Lopiano L. Levodopa-Induced Neuropathy: A Systematic Review. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2019;6(2):96-103.

This meeting was designed and delivered by the Parkinson’s Academy and sponsored by Bial Pharma. The sponsor has had no input into the educational content or organisation of this meeting.

Related articles

'The things you can't get from the books'

Parkinson's Academy, our original and longest running Academy, houses 23 years of inspirational projects, resources, and evidence for improving outcomes for people with Parkinson's. The Academy has a truly collegiate feel and prides itself on delivering 'the things you can't get from books' - a practical learning model which inspires all Neurology Academy courses.