Fractures in Parkinson’s: inevitability or neglect? – PD Cutting Edge Science

Event reports

This session is part of a series of write-ups on Parkinson's Cutting Edge Science for Clinicians 4; the conference summary for which is here. The conference was chaired by Dr Emily Henderson and Prof Annette Hand.

The penultimate session was delivered by Dr Veronica Lyell, consultant geriatrician at Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust. She provided a detailed discussion on fractures in Parkinson’s, posing the challenging question as to whether they are an inevitable part of Parkinson's and aging, or arise as a result of neglectful care.

Dr Veronica Lyell

Her talk provided a fresh perspective on bone health in Parkinson's disease to a 'rapt audience' (fig 1) and included plenty of practical advice to support all delegates in making positive changes to their practice on leaving the conference hall.

Terrific presentation from Veronica Lyell on fractures, bones and Parkinson’s disease.

— Sandy Thomson (@DrSandyThomson) October 5, 2021

Practical advice, clearly conveyed to a rapt audience

Need to embed risk assessment in routine clinic practice. @TheNeuroAcademy #pdces4

Figure 1: Tweet from consultant geriatrician and delegate Dr Sandy Thomson via handle @DrSandyThomson

In addressing what she termed this 'brutally dichotomous choice', Veronica examined the epidemiology of fractures in Parkinson's, whether there is an increased risk and if so, how this can be reduced, and what the consequences of a fracture can be in a Parkinson's patient. She also discussed what can cause 'neglect' leading to fractures in Parkinson's care, how to assess and manage risk of fractures in those with Parkinson's, and embedding this into mainstream practice.

Are fractures inevitable?

Veronica began by looking at fractures in the general populace, noting that they are a likelihood for many people. Indeed, she noted, a woman who reaches her 50's has a 1 in 3 lifetime chance of sustaining a future osteoporotic fracture, whilst men have a 20% chance (TP van Staa 2001; ZA Cole 2009). With this, Veronica was clear that this refers to a significant and impactful fracture which may have postural or movement implications going forward.

Dr Veronica Lyell

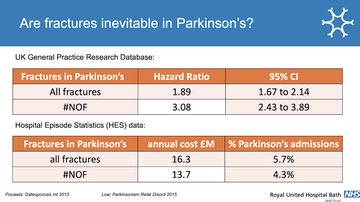

Veronica is clear that the consequences of fractures are impactful for both the patient and the health service itself, with fractures making up a third of hospital admissions for people with Parkinson's, with hip fractures alone accounting for 4% of Parkinson's admissions (fig 2), costing the NHS £14 million each year.

Figure 2: Slide from Veronica's presentation examining data of fractures in Parkinson's

It's not all about falls...

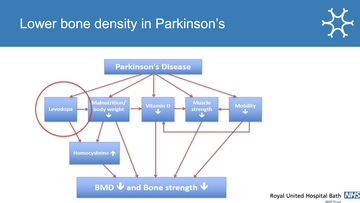

Veronica discussed the trauma that accompanies a fracture such as a fall, and highlighted the high risk of falls in Parkinson's. However, this is not the only risk of fracture, with bone health another risk factor in Parkinson's (fig 3) - with many contributing factors for this (fig 4).

Dr Veronica Lyell

Why do we neglect risk assessment?

— Emily Henderson (@DrEmHenderson) October 5, 2021

1. Patients don’t recognise it - esp for men because of dominant advertising that OP affects women.

2. It’s for primary care’ but it’s a specialist risk so needs spec input.

3. Concept of OP and need to move to fracture RISK instead

Figure 3: Tweet from co-chair Dr Emily Henderson commenting on bone health in Parkinson's resulting from Veronica's presentation

Veronica highlighted that vitamin D deficiency may be a precursor to Parkinson's with people found to have lower levels decades prior to diagnosis. She also noted that bone mineral density is not only related to vitamin D but to multiple factors including weight bearing and medication use.

Figure 4: The contributing factors to lower bone density in Parkinson's - slide from Veronica

She also shared that the consequences of a fracture for a person living with Parkinson's are more impactful than for the general populace.

Dr Veronica Lyell

What can we do about this inevitable risk?

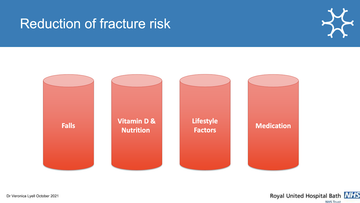

Veronica talked about the four pillars required to address fracture risk in people with Parkinson's and gave practical advice on these (fig 5). (This practical advice exempted falls, which she noted, could fill a full talk in and of itself!)

Figure 5: The four pillars to address in reducing fracture risk.

Noting that any adult at risk of fracture, of which people with Parkinson's are one group, are recommended to take 1000 units of vitamin D supplementation per day (SACN report 2016) . She noted that patients should have their vitamin D levels checked, and where deficient, should have these replaced by 300,000 units in a staged administration to support absorption. She suggested ensuring adequate calcium in diets, noting information from the Royal Osteoporosis Society.

With lifestyle, she highlighted load bearing and movement, as well as tobacco and alcohol use, and potential use of hip protectors, particularly in patients who are keen to increase their mobility but are nervous about doing so.

With medication, whilst there are a number of options, the most common, cheapest (£7.00 per year) and easiest medication is alendronic acid, which has a 40-70% risk reduction of fractures if taken in a sustained way over two-three years. She also shared a study in over 80's taking alendronic acid and a 50% reduction in hip fracture risk (Axelsson 2017). Where people have marked reflux or dysphagia it is not appropriate - and this does have implications for people with Parkinson's. Veronica shared that Adherence is the most challenging contraindication, but not one which cannot be overcome.

For those unable to tolerate alendronic acid, or unable to manage swallowing a tablet, zoledronic acid can be administered annually or every 18 months and can benefit someone for around a 5 year period. Experiencing flu-like symptoms (likely in 1 in 3 patients receiving the dose quickly in an outpatient environment) can be reduced by administering it slowly over an hour or so.

Are fractures ever caused by neglect?

Veronica referred back to her earlier comments around inevitability of fractures and the likelihood that, even with reduced risk across the four pillars (fig 5), reduction is only likely in up to 70% of cases. However, she pondered if neglect has a role in fracture reduction or management.

Dr Veronica Lyell

Veronica unpicked some of the reasons why fracture risk may not be assessed, beginning with a patient's own reporting, and suggesting that often they may not mention it with women with Parkinson's judging their risk to be lower than it is (GLOW 2009) and men often assuming it is a female-related concern.

She noted an assumption that GPs are responsible for managing this risk, but shared that, in addition to the challenges GPs are currently facing, Parkinson's and osteoporosis are specialist concerns and ought to be managed in a joint fashion, particularly for Parkinson's patients, by both specialists and GPs together.

Finally, she suggested that the concept of osteoporosis as a specialist disease and the requirements of assessing it can be a barrier to successful fracture assessment and management and shared the call to move towards fracture risk as a scale, rather than a specific diagnosis of osteoporosis.

How that risk is best assessed

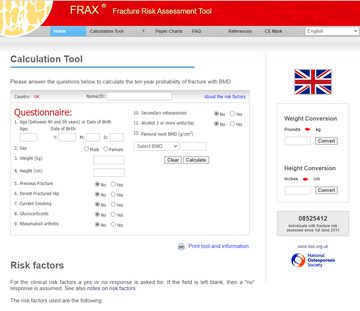

Suggesting that fracture assessment has never been easy and giving low-tech advice on how to create a false 'app' from it, Veronica introduced theFRAX assessment risk calculation tool (fig 6) and recommended every individual create a shortcut link to the webpage from their desktop.

Figure 6: The UK calculation tool page for FRAX, the fracture risk assessment tool, accessed https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.aspx?country=1

However, she notes that FRAX can disadvantage people with Parkinson's and men (although there is a button to press to add in the additional risks of Parkinson's, and Veronica shares how to find this)

This is because the tool uses major osteororotic fracture probability rather than hip fracture risk probability from the National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG) guidance (which will be reviewed soon and may then change). For women, this does not make much difference, Veronica notes, but for men, the hip fracture probability will make up the majority of their risk, and their risk will be discounted if only their major osteororotic fracture is looked at.

She noted that the number of men with hip fractures has continued to climb whilst the number of women is slowing, and suggested this is due to public health messaging about osteoporosis risk in women but not similar warnings for men.

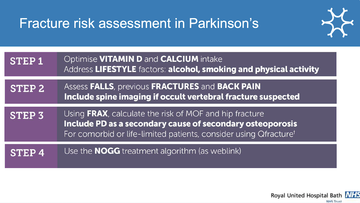

Veronica then shared her algorithm, BONE-PARK (2019) with 4 simple steps to follow (fig 7).

Figure 7: The 4 steps of the BONE-PARK (2019) algorithm for fracture risk assessment in Parkinson's

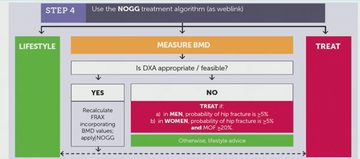

Veronica then used several case studies to talk delegates through the patient flow using the BONE_PARK algorithm and highlighting the management options which might be useful using the NOGG guidance as a treatment algorithm (fig 8).

Figure 8: The NOGG guidance as a patient flow within the BONE-PARK algorithm step 4

Ways to make improvement now

In closing Veronica mentioned the free online course for managing bone health in Parkinson's (approximately 10 hours of study time) available through the Parkinson's Excellence Network supported by Parkinson's UK.

She also highlighted the opportunity to work with Parkinson's UK audit on a service improvement project around bone health.

Finally she mentioned some of the changes to practice that people are already making to address and improve management of bone health in Parkinson's patients, including the simple act of adding a routine question on bone health to clinic questionnaires, making sure it is considered for all patients, in all follow-up appointments.

This meeting is designed and delivered by the Parkinson’s Academy and sponsored by BIAL Pharma. The sponsor has had no input into the educational content of this meeting.

Related articles

'The things you can't get from the books'

Parkinson's Academy, our original and longest running Academy, houses 23 years of inspirational projects, resources, and evidence for improving outcomes for people with Parkinson's. The Academy has a truly collegiate feel and prides itself on delivering 'the things you can't get from books' - a practical learning model which inspires all Neurology Academy courses.