Shining light on visual disturbances in PD and related conditions – PD Cutting Edge Science

Event reports

This session is part of a series of write-ups on Parkinson's Cutting Edge Science for Clinicians 4; the conference summary for which is here. The conference was chaired by Dr Emily Henderson and Prof Annette Hand.

Dr Rimona Weil, Consultant Neurologist & Clinician Scientist, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery addressed the conference, presenting 'Shining light on visual disturbances in Parkinson's and related conditions'.

Splitting her talk into two halves, Rimona began by considering how vision in Parkinson's can provide a clue to outcomes for that individual, before discussing visual hallucinations and how these might be managed well.

Excellent talk to close #pdces4 meeting by @rimonaweil - comprehensive review of #hallucinations in #parkinsons from mechanisms to potential treatment. Consider poor vision in #pd as a marker of poor outcomes, potentially modifiable

— Chris Kobylecki (@chriskobylecki) October 5, 2021

Why does vision matter in Pd?

Dr Rimona Weil

Rimona cited a range of studies forming part of the 'flurry of research' in the past 10 years highlighting this finding (Anang 2014; Williams-Grey 2013; Bohnen 2011). She went on to share that further research suggests that visual problems are also linked to worsening outcomes in Parkinson's including increased falls, depression, and mortality (Hamedani 2020; Gyule 2020).

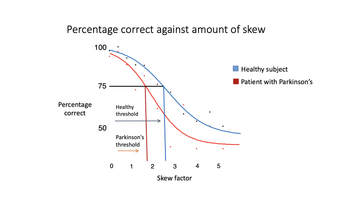

Based on this anecdotal evidence of a difficulty in people with Parkinson's in deciphering deliberately distorted images (e.g. CAPTCHA images of distorted numbers and letters), Rimona shared a study she conducted where people with Parkinson's were asked to review 400 distorted pictures of dogs and cats. She queried the 'skew' factor - the point where the picture is skewed to the degree that it can no longer be deciphered as the object it is.

Figure 1: Results of people with Parkinson's and skewed visual perception versus a healthy subject

She found that patients with Parkinson's had an earlier threshold of skew - the point at which they could not identify the animal was earlier than in health subjects.

Rimona went on to discuss her 'VIP study' - Vision in Parkinson's and what the study involved initially. She was able to share how, based on the work within VIP, that if a person has poor vision at baseline, and has Parkinson's disease, that there will be breakdown in white matter, specifically structural connections and particularly in the corpus callosum; something that can be picked up with a form of diffusion imaging (Zarkali & Weil 2020; Zarkali & Weil 2021).

In practice, Rimona shared that this can be helpful knowledge regarding anticipating a person's outcomes, adding to other known risk factors for poorer outcomes, particularly cognitive, in people with Parkinson's (Lui 2017; Shrag 2017).

These potential risk factors for dementia include:

having an older age at outset

being male

having depression

REM sleep behaviour disorder

poor vision (e.g. diplopia, difficulty reading)

Why does knowing this help?

Rimona discussed that knowing someone has risk factors for poorer outcomes can encourage implementing interventions, lifestyle behaviours and treatments to address these and reduce risk where possible. She mentioned various interventions such as encouraging exercise, referring back to Jonny Acheson's talk and to Bas Bloem's work) and addressing vascular health, as well as the importance of treating depression.

Hallucinations in Parkinson's

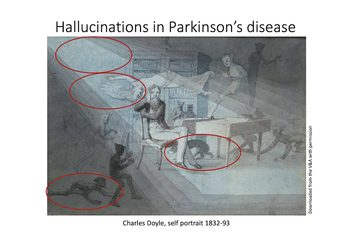

Rimona went on to discuss that specific element of visual disturbance common to people with Parkinson's: hallucination. Opening this section of her talk with an image, a self-portrait by Charles Doyle (father of Arthur Conan-Doyle), and noting that he did not have a diagnosis of Parkinson's or anything similar - and that Lewy body disease 'had not been invented yet' - she queried his health and highlighted a number of features in the picture which resonated with her understanding of hallucinations in Parkinson's disease (fig 2).

Figure 2: Charles Doyle's self-portrait resonates with our understanding of Parkinson's hallucinations

The areas circled were highlighted by Rimon specifically and include an imp on the floor, a dog under the table, images in the peripheral vision, and all viewings within a dim light. She played a video of a lady with Parkinson's eloquently discussing the hallucinations of people who she sees in her home between around midday and midnight most days.

Rimona explained that prevalence of hallucinations is around 60% in Parkinson's, that they are troublesome and increasingly so as the disease progresses, with individuals losing their clarity over whether they are real or not, and that they are the strongest predictor for a person with Parkinson's being admitted into residential care. They are also a predictor of poor outcomes and linked with a higher risk of mortality.

What causes hallucinations?

Rimona discussed the reasons for hallucinations, giving clarity around what is occurring in the brain to bring them about. She explained that visual acuity is often reasonable in those with hallucinations but that they will have higher order visual dysfunction (Gallagher 2011).

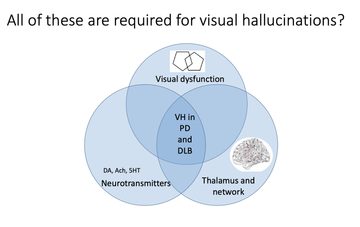

She suggested there are a number of elements which may impact hallucinations, outlining each and posing the question that perhaps, rather than separate causes, hallucinations may occur where all of these elements coexist (fig 3). The elements she shared are:

Neurotransmitters such as dopamine may be at play, with the brain recognising an increased salience of this neurotransmitter (Frith & Fletcher 2009).

Acetylcholine and the importance of addressing anticholinergic burden in patients with Parkinson's (ACB calculator) .

Serotonin and its role in 'sensory gating and precision' mentioning both that clozapine acts on serotonin receptors, and that these receptors modulate GABA - lower levels of which are found in the visual cortexes of those who hallucinate (Firbank & Taylor 2018).

Structural connectivity (as discussed earlier in the talk) as well as highlighting that there is a sub-network of connectivity in the brains of hallucinators specifically affecting areas like the thalamus and affecting switching between different states (Zarkali & Weil 2020)

The thalamus and its specific role in hallucinations, particularly its connections with the frontal part of the brain (Zarkali & Weil 2021; de Morsier, 'les hallucinations' 1938).

Figure 3: The neurological reasons for hallucinations - a combination of several simultaneous occurrences in the brain?

Effective management

Rimona shared that much of hallucination management comes down to being a good physician - asking questions, monitoring drugs and making sure that treatment is only considered if the individual is becoming troubled or upset by their hallucinations.

Dr Rimona Weil

Medication management is key, including withdrawing Parkinson's medications and whilst there is not clear guidance on how to do this Rimona mentioned a review by Connelly and Lang (2014) which helpfully suggests removing the least efficacious first, and reviewing anticholinergics early on.

The best evidence for antipsychotics is clozapine, however Rimona noted that this is not an easy drug to use, and is often difficult to get access to for patients with Parkinson's.

Rimona noted that quetiapine is the recommended first line treatment, yet the evidence for this is less compelling and it is first line because of the difficulties in accessing clozapine. She also mentioned olampazine, noting that whilst there is no evidence available in terms of a randomised controlled trial, she has found it effective on occasion when prescribing it in consortium with a psychiatrist.

Horizon-scanning for medications

Pimavanserin, not yet licensed in the UK and very expensive, has been found to be well-tolerated and to reduce hallucinations in number (Cummings 2014) whilst those with a lower cognitive ability appear to have greater benefit (Espay 2018).

Ondansetron, which has been available as a treatment for nausea for some time, was found to be beneficial for people with Parkinson's and hallucinations when an open-label study examined its use in Parkinson's in the 1990's. However, there has yet to be a randomised-controlled trial in its use; Parkinson's UK has now offered to support a trial for TOPHAT examining Ondandetron in Parkinson's patients with hallucinations, and is currently recruiting to 25 sites around the UK. Rimona noted that this trial is being extended to include people with Lewy body dementia as well.

This meeting is designed and delivered by the Parkinson’s Academy and sponsored by BIAL Pharma. The sponsor has had no input into the educational content of this meeting.

Related articles

'The things you can't get from the books'

Parkinson's Academy, our original and longest running Academy, houses 23 years of inspirational projects, resources, and evidence for improving outcomes for people with Parkinson's. The Academy has a truly collegiate feel and prides itself on delivering 'the things you can't get from books' - a practical learning model which inspires all Neurology Academy courses.